As this article shows even one of the world’s most autocratic and corrupt leaders wants popular voting to give authority to his party’s rule. Might makes right, but it doesn’t create the appearance of justification for political power and it is inherently unstable.

If he thought about it creatively, Putin could consider adapting the American electoral college system to his purposes. In the United States the people don’t pick the president by vote. They are only told that they do.

Instead they pick electors, who, under the 10th Circuit’s decision in Baca v. Colorado Department of State, can choose anyone they want for president. Political parties nominate electors by opaque processes. It is reasonable to suppose that every elector has made or received sizable political donations in order to be noticed by the nominators. They are quintessential apparatchiks.

Perhaps to avoid embarrassment or to convince voters falsely that they are choosing the president, many states do not reveal the names of electors on the ballot. Even where they are identified the only voters sure to know them are their family members.

The electors from different states do not deliberate. They do not even meet with each other. Yet they are described as attending an electoral college. This college has no courses, instructors, or degrees. But the description persuades some otherwise reasonable people that this nonexistent institution effects a ratiocinative process for choosing the nation’s leader.

Just as mind-boggling is the way many people, including judges, think that history should command the country to perpetuate this process. In brief, it is thought by many that the writers of the Constitution wisely designed a system unchangeable for the ages when they imagined white men from 13 eastern seaboard states would travel by horseback for about four to five weeks to Philadelphia (or later, Washington) in order to negotiate on which slaveholder or slavery-tolerating person a majority of them would accept for president.

Electors are also described as representing the interests of thinly populated states (most in French territory at the time of writing the Constitution, so not contemplated as stakeholders by the framers). But it’s a good bet not one elector knows soy from sorghum and that all or almost all live in cities or suburbs. At any rate, we know that not a single elector has a published farm policy or a “small state” policy.

To top it off, the media collaborates enthusiastically with politicians in convincing the American people that their votes matter and that the system serves the best interests of the whole country.

How could Putin not win his elections with this method?

And if Russians could be convinced as easily as are many Americans that they actually had voted in a fair and meaningful way then he would have the legitimacy he craves for his exercise of autocratic control.

Just a thought.

What do to about Baca, part 2

"If the law supposes that," said Mr. Bumble, squeezing his hat emphatically in both hands, "the law is a ass - a idiot". -- Charles Dickens, in Oliver Twist.

The Baca decision holds that the framers intended for electors to decide as independent agents who should be the president and who the vice president. Each state has unfettered authority to decide how to appoint electors—by vote of the people, by vote of the legislature, by lot, by the machinations of horoscopes or ouija boards ("spirit of George Washington, who should be president?"), by sale to the highest bidder.

Could a state really sell elector seats? That's a law school question that may need to be answered in real existing politics.

Anyhow, other courts may agree or disagree with Baca, and perhaps the United States Supreme Court will have something to say about this matter. Surely it's important for everyone to know well in advance of the November 2020 election whether Americans are actually voting in a reliable, meaningful way for president or vice president, or whether instead they are delegating that choice to electors.

If the Constitution means that voters are merely delegating the important choice to electors, then people deserve to know a lot more about who is taking on this important job.

Many states do not even list the electors on the ballot. Even if on the ballot, they do not campaign. They do not explain why they deserve to be trusted with the responsibility to pick the nation's only two national government executives. To set forth their qualifications, they are going to need to raise money. The candidates for president in 2020 will spend, all in, a total of $3 to $4 billion on presenting their merits. If the voters are not in reality choosing among the parties' nominees, then all that money perhaps should be spent to present the electors to the voters. The electors themselves do not have to choose among the nominees of the parties anyhow, so there is little purpose to the political spectacle that we currently call the presidential race.

If the Baca becomes the law of the land, people leaning left and right on the political spectrum should agree that this law creates an ass of a system. The obvious alternative is to let the voters directly pick the president. Do not blame the Baca court. Instead, recognize that it's high time to amend the Constitution's broken, antedated, and otiose method of choosing the president.

American history reveals a halting, sometimes wandering, but always vital expansion of democracy. The Baca reading of the framers' intent may be right. But in that case, the framers' conception at last should be updated to reflect the virtue, indeed the necessity, of a truly democratic process for choosing the nation's two top leaders.

In this process, step one is to decide if the candidates for president should be highly encouraged to campaign everywhere for everyone's vote. If the answer to that is yes, then the national vote must choose the president, instead of the current system according to which a handful of swing states attract all attention and distort policies and governance away from the desires of most people.

Step two is to decide if every vote cast nationally should be of equal weight. It could be thought that the composition of the Senate, which cannot be changed by constitutional amendment, suffices to protect the interests of small states. In that case, there's no reason to give small state voters more weight in picking the president than voters in big states. But if the small states' officials want to demand greater voter weight in order to compromise on a constitutional amendment, then every voter can have their votes weighted according to the relative population of the state in which their vote is cast.

Step three is to make up the national mind about whether the president should always be chosen by majority vote, as opposed to having most people vote against the person as occurs fairly often. To produce a majority for the president, the United States would need to adopt some sort of run-off, either instant (also called ranked choice) or a two-stage voting method.

Finally, in the amendment, the country could throw away the obviously anti-democratic back up methods of the Constitution, election by the House where each state has one vote or election by the Senate.

Baca presents anew the long-bruited, extremely obvious fact about the American system of choosing the president. It is terribly flawed. It does not serve either party well, and harms the whole country in numerous ways. The Baca judges are not idiots. They intended only to describe what the framers intended. The system, which did not work beyond the Washington Administration, has become more and more idiotic as the country has grown and changed. When the law is this much of an ass, it's incumbent on all of us to change it.

Invitation to Extreme Unpredictability: Summary of Baca v. Colorado Dep’t of State (10th Cir. 2019)

The United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit just reached a decision that expands the anti-democratic nature of the Electoral College into a new realm of unpredictability.

If this decision becomes the law of the land, then electors chosen by popular vote in a state, or by a national popular vote if that reform goes into effect, can ignore the voters and pick the president and vice president of their choice. They do not even have to choose between the candidates nominated by the two parties. An elector can pick anybody he or she likes.

The court felt that the framers of the Constitution intended to give electors this unfettered power. In the current century, this reading of original intent leads to many startling possible scenarios, including the use of unlimited funds and unthinkably powerful advertising techniques to persuade any and all of 538 electors that someone not chosen by the people of any state, much less the whole country, should be president.

Here follows a summary of the decision:

Plaintiff Michael Baca was a presidential elector appointed in Colorado, which, by statute, required its electors to vote for the winner of the popular vote in that state. Colo. Rev. Stat. § 1-4-304(5). Even though a majority of Coloradans voted for Clinton, Mr. Baca attempted to cast his vote for John Kasich on the date that the electors met to cast their votes. The Colorado Secretary of State removed Baca as an elector, and replaced him with a substitute elector who voted for Clinton.

Baca sued under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for an alleged deprivation of his constitutional rights provided by Article II and the Twelfth Amendment. The Tenth Circuit found that Baca had standing to challenge Colorado’s statute. The court further found that the “state’s removal of Mr. Baca and nullification of his vote were unconstitutional.” Baca, at 2.

The court framed the question as “whether the states may constitutionally remove a presidential elector during voting and nullify his vote based on the elector’s failure to comply with state law dictating the candidate for whom the elector must vote.” Id. at 63. The court found that although the Supreme Court has not ruled on the question directly, it has stated in dicta, concurrences, and dissent, that the original intent of the Constitution “recognized elector independence.” Id. at 66.

Colorado argued that “the power to bind or remove electors is properly reserved to the States under the Tenth Amendment.” Id. at 76. However, the court rejected the argument that the power to bind electors was “reserved” to the states under the Tenth Amendment “because no such power was held by the states before adoption of the federal Constitution.” Id. at 77. Accordingly, “The Tenth Amendment thus can provide no basis for removing electors or canceling their votes . . . .” Id. at 78. Because the Tenth Amendment did not reserve the power to nullify the vote of a presidential elector, the court framed the question as “whether the Constitution expressly permits such acts.” Id. at 78.

The state, relying on the president’s power to remove officials, argued that “the power to appoint necessarily encompasses the power to remove.” The court disagreed. Though the court acknowledged that “the state legislature’s power to select the manner for appointing electors is plenary,” id. at 79 (quoting Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98, 104 (2000)), it did not follow that the state also had “the ability to remove electors and cancel already-cast votes after the electors are appointed and begin performing their federal function,” id. The court distinguished presidential appointees, who are subordinate officers in the electoral branch and thus under the president’s control, from electors, who perform a separate federal function from the states that appoint them

The court found that “Based on a close reading of the text of the Twelfth Amendment, we agree that the Constitution provides no express role for the states after appointment of its presidential electors.” Id. at 84. The court noted that “From the moment the electors are appointed, the election process proceeds according to detailed instructions set forth in the Constitution itself,” and “Nowhere in the Twelfth Amendment is there a grant of power to the state to remove an elector who votes in a manner unacceptable to the state or to strike that vote.” Id. at 86. The court concluded that “while the Constitution grants the states plenary power to appoint their electors, it does not provide the states the power to interfere once voting begins, to remove an elector, to direct the other electors to disregard the removed elector’s vote, or to appoint a new elector to cast a replacement vote.” Id. at 86-87. In other words, because the Constitution does not give the states an explicit right to remove electors or control their votes, no such right exists.

The court looked the words “elector,” “vote,” and “ballot,” and found that these terms, as they would have been understood at the time of the adoption of Article II and the Twelfth Amendment, established that no role for the state existed beyond the appointment of electors. Id. at 88. The court found that contemporaneous dictionaries reflect that “the definitions of elector, vote, and ballot have a common theme: they all imply the right to make a choice or voice an individual opinion.” Id. at 90. The court also looked at the term “elector” as it is used elsewhere in the Constitution, and found that “electors” in Article I and the Seventeenth Amendment “exercise unfettered discretion in casting their vote at the ballot box.” Id. at 92. The court also found that the Federalist Papers were “conclusion that the presidential electors were to vote according to their best judgment and discernment.” Id. at 105-09.

The court noted that there had been a longstanding practice of requiring electors to pledge to vote for a certain candidate. However, the court found that the fact that Congress had previously counted every “anomalous” vote that had ever previously cast, pledges notwithstanding “weighs against a conclusion that historical practices allow states to enforce elector pledges by removing faithless electors from office and nullifying their votes.” Id. at 101.

Nor did the fact that most states do not even list their electors on the ballots change the court’s conclusion that interference with an elector was unconstitutional. Id. at 101-105. The court noted that the Supreme Court had found that “[t]he individual citizen has no federal constitutional right to vote for electors for the President of the United States unless and until the state legislature chooses a statewide election as the means to implement its power to appoint members of the electoral college.” Id. at 104 (quoting Bush, 531 U.S. at 104). Accordingly, even though all states now allow the citizens to vote for presidential electors the state “can take back the power to appoint electors.” Id. (quoting Bush, 531 U.S. at 104). The court found that, similarly, “Although most electors honor their pledges to vote for the winner of the popular election, that policy has not forfeited the power of electors generally to exercise discretion in voting for President and Vice President.” Id.

In conclusion, the court found that the Secretary of state “impermissibly interfered with Mr. Baca’s exercise of his right to vote as a presidential elector” by “removing Mr. Baca and nullifying his vote for failing to comply 114 with the vote binding provision in § 1-4-304(5). Mr. Baca has therefore stated a claim for relief on the merits, entitling him to nominal damages.”

The Electoral College at Work

From Axios newsletter August 9:

“Trump campaign officials and sources close to the president tell Axios that they believe Democrats' extraordinary charge that the president is a ‘white supremacist’ will actually help him win in 2020, Axios' Alayna Treene reports.”

If true, this is the electoral college at work. There is no way that this “charge” would help any candidate who had to win the national popular vote. But the demographic mix of the handful of swing states is quite a bit different than the rest of the country, and so this alleged claim by “sources close to the president” could be what they really think.

The Electoral College, of course, has its roots in the country’s attitude toward race. By extending the disproportional power given to the slave states in the House into power of the choice of the president, the system virtually assured that presidents would not limit the perpetuation and even expansion of slavery. This worked until 1860, after which the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments gave the Confederate states still more weight in the House by counting former slaves fully, even while they had little to no chance of sending an elector to vote for the president they wanted.

In different ways now, the Electoral College still tilts the scales of political power against people of color.

Thanks, Electoral College

Almost all the voters in the problem locations below are ignored by the system. Florida, it gets attention, and sometimes North Carolina. But the candidates in both parties take for granted the outcome all the rest of these states. Given the plight of the people in these states, the voters really ought to be able to have all their votes count in a national election of the president.

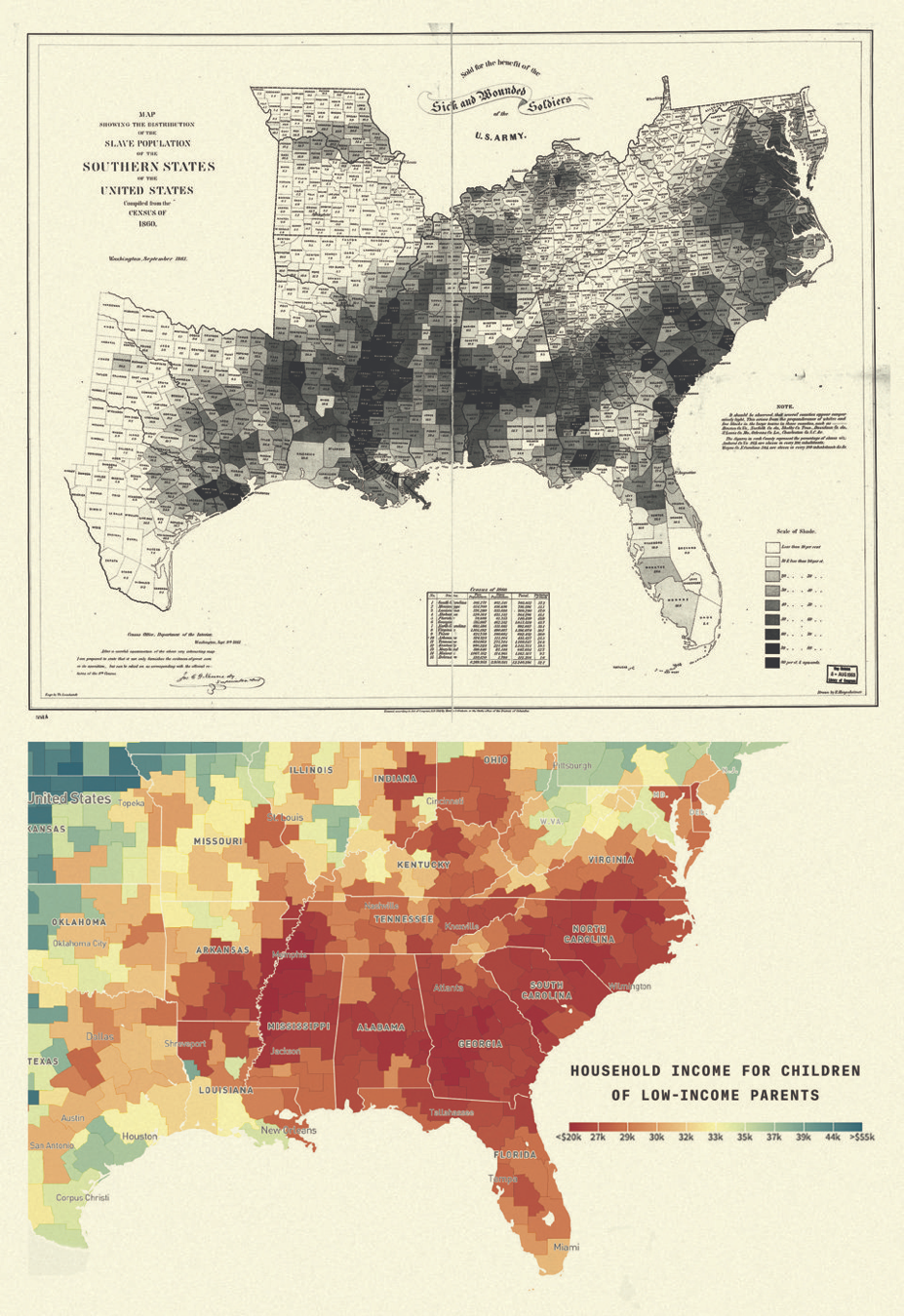

There are two maps shown. The first is Lincoln’s, used to inform him about the slave population. The second, is Raj Chetty’s report on where low income parents are located. The overlaps show, among other things, how long the Electoral College system has denied voice to the people – of all races! – in these states.

A Look Back on a Bipartisan Effort to Reform the Electoral College

Recent polls have shown a sharp partisan divide in American’s opinions about Electoral College reform, though a majority still prefers a national popular vote. But the national popular vote was not always an issue that split along partisan issue. Polls from the 1960s and 1980s showed that large majorities of Republicans and Democrats both favored a national popular vote in nearly equal numbers.

During that era, there was a robust effort to reform the Electoral College by constitutional amendment spearheaded by Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana. As Jesse Wegman wrote in the New York Times:

In a remarkable speech on May 18, 1966, Mr. Bayh said the hearings had convinced him that the Electoral College was no longer compatible with the values of American democracy, if it had ever been. The founders who created it excluded everyone other than landowning white men from voting. But virtually every development in the two centuries since — giving the vote to African-Americans and women, switching to popular elections of senators and the establishment of the one-person-one-vote principle, to name a few — had moved the country in the opposite direction.

Adopting a direct vote for president was the “logical, realistic and proper continuation of this nation’s tradition and history — a tradition of continuous expansion of the franchise and equality in voting,” he said.

He then explained how the Electoral College was continuing to harm the country. The winner-take-all method of allocating electors — used by every state at the time, and by all but two today — doesn’t simply risk putting the popular-vote loser in the White House. It also encourages candidates to concentrate their campaigns in a small number of battleground states and ignore a vast majority of Americans. It was no way to run a modern democracy.

Despite having the support of more than 80% of the population according to a 1968 Gallup poll, the effort to amend the Constitution failed, as nearly all proposed constitutional amendments do.

Fortunately, with the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, an amendment isn’t required to make all votes matter.

Mark Bohnhorst on the History and Future of the Electoral College

The History of the Electoral College and the Modern Case for Reform

In an excellent piece published in the Minnesota Star Tribune, Mark Bohnhorst, chair of the State Presidential Elections Team at Minnesota Citizens for Clean Elections, combats some of the most pervasive myths about how the Electoral College was designed to work and how it actually works, as well as examining the likely implications of a national popular vote:

The Electoral College was clearly an unholy if necessary compromise with slavery. Even following the Civil War, the Electoral College crisis of 1876 helped perpetuate racial injustice by ending Reconstruction, which led to another century of racial subjugation.

…

[Under the national popular vote], candidates will seek votes wherever the voters are. They will not ignore 100 million voters — urban or rural. They will use technology to reach as many voters as possible as efficiently as possible. That feels like democracy — the kind of democratic republic James Madison would have approved.

What does Fixing a Bicycle have to do with Fixing our Destructive Presidential Election System?

To a striking degree, voters of different political persuasions agree that things are going wrong with our government and our political system. Shared national values are fraying as a result. Most voters agree on many of the things that are going wrong—hyper-partisanship, citizen distrust of government, intensive divisiveness, and a conviction that they are not being represented by the system. To be sure, they don't agree on how to reform the system, but fundamentally they do agree that it needs to be reformed.

When I was a kid growing up during World War II, the popular story line was that Americans were good at fixing things. When GIs landed in rural France they endeared themselves to the liberated villagers not only by handing out chocolates but also by repairing their bicycles. To fix a bicycle, one first needs to determine what is wrong with it and then roll up his or her sleeves to make the fix. That was the reputation Americans had, it was legitimately earned, and we were proud of it.

The same was true of our political system from the earliest days of our country. We did what we needed to make things work. Our founders were visionaries, it is true, but they were also practical. Europeans, by contrast, tended to be guided by ideologies and spent considerable time in ideological debate. This approach—from the divine right of kings, to the perfectibility of humankind, to communism's "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need," to the empty and cynical slogans of totalitarian states—got them into trouble.

In contrast, American political rallying cries—Teddy Roosevelt's "Square Deal," Franklin Roosevelt's "New Deal," and Harry Truman's "Fair Deal"—have been grounded in the practical mentality of the Yankee peddler. In addition to improvisation and practicality, these slogans reflected a commitment to fixing things, making them better.

As a country, we need to fix our political system, and it doesn't matter all that much, beyond certain fundamental values the great majority of Americans share, what collection of beliefs each participant brings to a table where the root causes of our problem are identified and remedies are fashioned by collaborative discussion and reciprocal horse trading.

Making Every Vote Count's leadership has come together from different political perspectives. Like a rapidly growing number of other groups and individuals, which are concerned about the serious problems in our political system, board members of disparate views on many issues are joined in the conviction that a major source of these problems is a very specific segment of our Presidential election system -- how 48 states allocate their electoral college votes under a very unrepresentative winner-take-all system -- not in the Constitution, itself, and that it is fixable. This defect is the equivalent of the broken bicycle chain that prevents it from being used properly.

So, let's put aside ideologies, but not our national values, put our hands into the grease of the malfunctioning bicycle chain and devise and implement the needed fix. That's what our founders did in 1787, when the damaging flaws of the Articles of Confederation had become apparent. The difference here, however, is that we don't have to throw away the old bike. We need to fix only the one defective part of it. In the case of our Presidential election system, an increasing number of commentators, scholars, and public and political figures recognize that the appropriate remedy can and should be implemented at the state level, not at the level of the federal government. We should get on with the job.

Yes!

This article by Yale Law School Professor Akhil Reed Amar has it right. The Electoral College is not something to be venerated. It is a shame that the framers had to adopt this system to get the necessary votes from slave states to ratify the constitution. It’s a further shame that it has existed for the last two centuries plus.

The reasons sadly have a great deal to do with the fact that the history of America is the history of race.

We don’t need to have a constitutional amendment to extirpate this system from the future of America.

Just appointing a big enough bunch of electors who are bound to the national popular vote winner will be sufficient to cause campaigns to compete nationally. Then this particular element of national disgrace will be erased.

The part Professor Amar has wrong is his unsupported statement that there are reasons to keep the electoral college system. He does not cite any. There aren’t any.

Debunking Myths About the National Popular Vote

The Week debunks several of the most prominent arguments against the National Popular Vote, including that the current system is working the way the Founder Fathers envisioned, that candidates would ignore small states, and that change is impossible.

Let All the People Pick the President

Numerous Democratic presidential candidates want to get rid of the Electoral College. On the other hand, the only Republican candidate says that the system is “brilliant” because if all citizens in a single national vote chose the president then he and his rival Democratic nominee would pay no attention to anyone living in a small state or the Midwest.

Everyone can see that the Democrats believe their nominee would win the national popular vote, and President Trump, having said he could have won in 2016, might not be confident that he could pull that off in 2020. Nothing is surprising about politicians wanting rules of the game that help them win.

But neither Republicans nor Democrats are mentioning the three sins of the current system. Regardless of which candidates a national popular vote would favor, these clearly call for abandonment of an 18th century system designed to protect slavery and solve the logistical problems of travel in a pre-telegraph era.

First, because the pluralities in more than 40 states are predictable in these tribal times, in the general election the two major party campaigns ignore those states in which more than 80% of Americans live. Their indifference to turn-out in those states causes total voter participation to fall between 20 and 80 million votes short of the levels that would be reached if every vote counted in picking the president. Disinterest and disgust come from voter indifference – people who know they are ignored justly harbor resentment that undermines trust in government.

Second, because the general election presidential campaigns don’t pay much attention to four out of five Americans, the parties and their nominees do not offer promises, platforms or policies that most Americans want. Huge majorities register their desire for sensible compromises and good legislation on immigration, infrastructure, clean power, better support for child care and a host of other common-sense measures. The candidates don’t need votes from most people, so they don’t pay attention to most people during the election cycle and then when in office.

Third, because the result in presidential election is dictated by small margins in perhaps only four states – currently, Florida, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin – billions of dollars are spent by the two parties in badgering voters and wooing political leaders in these states. The politicians might enjoy the attention. The people in those states do not. They get little or nothing out of robocalls, door knocks, and Facebookery that mark over-intensive campaigning. In Iowa or New Hampshire in the primaries voters actually get to meet the candidates. From September to November every four years the proverbial swing voters just get digitally bludgeoned.

To build some trust between the people and the politically powerful, to give most people what most people want out of government, and to spread the pain of political campaigns fairly and more bearably over the whole country, it is time to let the people pick the president.

Legal Scholar Paul Smith Makes the Case for the National Popular Vote

From the Campaign Legal Center:

“Under the U.S. Constitution, states have the power to determine how they award their electoral votes in national elections. States are increasingly showing that the will of their voters is to do away with the winner-take-all laws, which award all of its electoral votes to the presidential candidate who receives the most votes within the state. They are signing up for the National Popular Vote Compact.”

Twenty Questions About the National Popular Vote

White Supremacy’s Anvil: The Electoral College

Take a look at this illuminating history of the Electoral College from Making Every Vote Count Co-Founder and CEO Reed Hundt on Medium. It discusses how the Electoral College was conceived to protect the institution of slavery, and how the Electoral College worked to create and preserve Jim Crow long after slavery was officially abolished.

Demography and Democracy

In “No Property in Man,” historian Sean Wilentz explains that the southern representatives to the constitutional convention were disappointed to see rather quickly that the “widely expected movement of population to favor the south and southwest never occurred, as settlement of migrants and new immigrants disproportionately favored the North.” Page 187.

In 1800, free states had 76 members of Congress, and slave states had 65. But by 1820 the margin was 122 to 90.

Southerners had hoped that the three-fifths compromise coupled with a swelling slave population would give them a slaveholding majority in the House. In that event, the Electoral College would always produce a pro-slavery president, even while slaves could not vote.

But demography is destiny. The burgeoning population of the North rapidly gave the House more free state representatives despite the three-fifths compromise.

Now again, as in first decades of the Republic, the demographic trends of the country are rapidly filling the House with members who root out and oppose racism in all its many manifestations, whether blatant or insidious.

These same trends have not yet changed the method of selecting the president. This is the reason that racially divisive candidacies for that high office are still possible.

ICYWTK

Someone asked me the other day what I most disliked about the Electoral College system (that any state law can change). Huge is the fact that the system virtually forces the candidates to ignore the views of the vast majority of Americans. But here's the whole list of what disturbs your correspondent.

1. Makes the views of most Americans irrelevant to presidential candidates. The Electoral College system creates swing states—they are accidents of demography, states where the balance of right and left leaning voters by happenstance is roughly equal. Most state populations tilt one way or the other. These are the ignored states, because the candidates know who will win the plurality. But more than 80% of Americans live in the land of the ignored. There strong majorities support more government action on infrastructure, shift to clean power, limitations of the size of magazines in assault weapons, the well-off paying a higher percentage of their income in taxes than the middle to lower income households, more government support of higher education so college doesn't cost an arm and a leg, and immigration reform to give clarity to millions of people about whether they can or cannot ever become citizens. The Electoral College system motivates the candidates to appeal to the views of the few and ignore the wishes of the many.

2. Bad for Black Americans. The framers of the Constitution designed the Electoral College to make sure that no abolitionist could become president. When Lincoln got elected in 1860, and the civil war ensued, in the aftermath the former Confederate states in the south adapted the system to make sure that all electors from their state represented white supremacists and no former slaves could ever send an elector to choose the president. To this very day that same system suppresses the relevance of African American votes in almost every election. This is why Barack Obama got zero electors from South Carolina to Texas—right across the heartland of the old Confederacy.

3. Unfair to women. The Electoral College is biased against women. More women vote than men. Women turned out a bigger majority for their preferred candidate than men did for theirs. But somehow the choice of males got elected in 2016 and 2000. Why? The Electoral College made the election turn not on the views of the whole country but only on the skinny margins of a handful of states where the views of women were felt a little less strongly than in the whole country.

4. Treats legal immigrants as second class citizens. The Electoral College is biased against immigrant citizens even to the second generation. Most immigrants live in just five states—the states that are portals to the country. In all these five except Florida the candidates of both parties take the election results for granted, and so they ignore the wishes of immigrants. And in Florida the immigrants who matter most matter are Spanish speakers not from Mexico. No candidate could campaign about a wall or rail against immigration except for the unfairness of the Electoral College.

5. Throws shade on workers. The Electoral College is biased against workers who hold jobs located mostly in the 40 states that are taken for granted. Loggers and longshoremen for example are ignored while coal miners get lots of attention. Why? Coal miners live in swing states. The others don't. This unfairness exists only because every vote does not matter—hardly any votes matter except those in swing states.

Right, Professor, Right

In his book “No Property in Man,” historian Sean Wilentz writes of the Constitution’s Framers, “On July 20, the delegates gave their initial approval to what might have been the most decisive triumph on behalf of slavery of the entire convention….the creation of the Electoral College.” Page 70.

The Electoral College was conceived in the sin of slavery. No one now argues that slavery was anything other than a horrible proof of the depravity of human beings. Holding on to it was the single strongest motive of the southerners at the convention.

As Wilentz writes, “the convention divided between those more and those less impressed by the competence of popular rule,” but beyond doubt “southerners in both groups had an additional reason to oppose popular election of the president.”

What was that? And does it still lurk in the thinking of those who oppose direct election by national popular vote of the president? See, e.g., former Maine Governor Paul LePage, who oppose direct election because it would empower non-white voters.

Wilentz explains that because slaves would not be able to vote, “southerners were unlikely ever to win the presidency under a democratic system.”

Even today, more than 200 years later, African American voters in the south typically play little to no role in the general election of the president – because the electoral system systematically discards the votes for runners-up, which usually is where the non-white vote in the polarized south goes:

To win the southern states’ agreement to vote for the constitution, Madison apportioned the electors according to total of the seats in the House, which gave weight to slaves on a three-fifths basis, and seats in the Senate, which gave weight to relatively underpopulated states (which came to include more slave states, like the nearly empty Florida and Arkansas). The unsurprising result, Wilentz explains, was that “four of the first six presidents of the United States were Virginia slaveholders.” He might have gone on to say that no president was anti-slavery until Abraham Lincoln in 1860. And Lincoln won only because the Democratic Party split between northern and southern factions.

The history of America is the history of race and the principal arguments for the Electoral College system today are, whether or not well-intentioned, all too clearly resonant of the views of the southern delegates in the 18th century and Governor LePage this week.

Wait - Why Don’t All Votes Count?

Here’s a primer on how we elect our presidents—and why most people’s votes are systematically thrown away.

The Electoral College "Has Not Stood The Test Of Time"

In an excellent piece in the New York Times, Jamelle Bouie explains that the Electoral College has almost never worked as it was intended, and states the case for making a change:

The history of the Electoral College from [1800 on] is of Americans working around the institution, grafting majoritarian norms and procedures onto the political process and hoping, every four years, for a sensible outcome. And on an almost regular schedule, it has done just the opposite.

…

Americans worried about disadvantaging small states and rural areas in presidential elections should consider how our current system gives presidential candidates few reasons to campaign in states where the outcome is a foregone conclusion. For example, more people live in rural counties in California, New York and Illinois that are solidly red than live in Wyoming, Montana, Alaska and the Dakotas, which haven’t voted for a Democratic presidential candidate in decades. In a national contest for votes, Republicans have every reason to mobilize and build turnout in these areas. But in a fight for states, these rural minorities are irrelevant. The same is true of blue cities in red states, where Democratic votes are essentially wasted.

Candidates would campaign everywhere they might win votes, the way politicians already do in statewide races. Political parties would seek out supporters regardless of region. A Republican might seek votes in New England (more than a million Massachusetts voters backed Donald Trump in 2016) while a Democrat might do the same in the Deep South (twice as many people voted for Hillary Clinton in Louisiana as in New Mexico). This, in turn, might give nonvoters a reason to care about the process since in a truly national election, votes count.