See the latest from MEVC board member James Glassman and CEO Reed Hundt on Real Clear Politics.

Polls show that Trump could lose the national popular vote by 10 million votes and still win the Electoral College

Our Presidential Selection System is Biased and Broken

Presidential elections where the winning candidate loses the national popular vote are becoming the new normal. It’s happened in two out of the last five elections, and would have happened again in 2004 if just 60,000 votes in Ohio had gone the other way. In future elections, we can expect a split between the electoral college and the national popular vote up to 30-40% of the time.

As Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne writes:

There is nothing normal or democratic about choosing our president through a system that makes it ever more likely that the candidate who garners fewer votes will nonetheless assume power. For a country that has long claimed to model democracy to the world, this is both wrong and weird.

And there is also nothing neutral or random about how our system works. The electoral college tilts outcomes toward white voters, conservative voters and certain regions of the country. People outside these groups and places are supposed to sit back and accept their relative disenfranchisement. There is no reason they should, and at some point, they won’t. This will lead to a meltdown.

Fortunately, we do not have to accept a status quo that routinely and systematically disenfranchises voters. Under the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, all votes would count equally—no matter who you are or where you live.

What do to about Baca, part 2

"If the law supposes that," said Mr. Bumble, squeezing his hat emphatically in both hands, "the law is a ass - a idiot". -- Charles Dickens, in Oliver Twist.

The Baca decision holds that the framers intended for electors to decide as independent agents who should be the president and who the vice president. Each state has unfettered authority to decide how to appoint electors—by vote of the people, by vote of the legislature, by lot, by the machinations of horoscopes or ouija boards ("spirit of George Washington, who should be president?"), by sale to the highest bidder.

Could a state really sell elector seats? That's a law school question that may need to be answered in real existing politics.

Anyhow, other courts may agree or disagree with Baca, and perhaps the United States Supreme Court will have something to say about this matter. Surely it's important for everyone to know well in advance of the November 2020 election whether Americans are actually voting in a reliable, meaningful way for president or vice president, or whether instead they are delegating that choice to electors.

If the Constitution means that voters are merely delegating the important choice to electors, then people deserve to know a lot more about who is taking on this important job.

Many states do not even list the electors on the ballot. Even if on the ballot, they do not campaign. They do not explain why they deserve to be trusted with the responsibility to pick the nation's only two national government executives. To set forth their qualifications, they are going to need to raise money. The candidates for president in 2020 will spend, all in, a total of $3 to $4 billion on presenting their merits. If the voters are not in reality choosing among the parties' nominees, then all that money perhaps should be spent to present the electors to the voters. The electors themselves do not have to choose among the nominees of the parties anyhow, so there is little purpose to the political spectacle that we currently call the presidential race.

If the Baca becomes the law of the land, people leaning left and right on the political spectrum should agree that this law creates an ass of a system. The obvious alternative is to let the voters directly pick the president. Do not blame the Baca court. Instead, recognize that it's high time to amend the Constitution's broken, antedated, and otiose method of choosing the president.

American history reveals a halting, sometimes wandering, but always vital expansion of democracy. The Baca reading of the framers' intent may be right. But in that case, the framers' conception at last should be updated to reflect the virtue, indeed the necessity, of a truly democratic process for choosing the nation's two top leaders.

In this process, step one is to decide if the candidates for president should be highly encouraged to campaign everywhere for everyone's vote. If the answer to that is yes, then the national vote must choose the president, instead of the current system according to which a handful of swing states attract all attention and distort policies and governance away from the desires of most people.

Step two is to decide if every vote cast nationally should be of equal weight. It could be thought that the composition of the Senate, which cannot be changed by constitutional amendment, suffices to protect the interests of small states. In that case, there's no reason to give small state voters more weight in picking the president than voters in big states. But if the small states' officials want to demand greater voter weight in order to compromise on a constitutional amendment, then every voter can have their votes weighted according to the relative population of the state in which their vote is cast.

Step three is to make up the national mind about whether the president should always be chosen by majority vote, as opposed to having most people vote against the person as occurs fairly often. To produce a majority for the president, the United States would need to adopt some sort of run-off, either instant (also called ranked choice) or a two-stage voting method.

Finally, in the amendment, the country could throw away the obviously anti-democratic back up methods of the Constitution, election by the House where each state has one vote or election by the Senate.

Baca presents anew the long-bruited, extremely obvious fact about the American system of choosing the president. It is terribly flawed. It does not serve either party well, and harms the whole country in numerous ways. The Baca judges are not idiots. They intended only to describe what the framers intended. The system, which did not work beyond the Washington Administration, has become more and more idiotic as the country has grown and changed. When the law is this much of an ass, it's incumbent on all of us to change it.

More People Vote When They Know It Counts: A Case Study

Texas has been in the bottom five states for voter turnout for the past three presidential elections. In the 2016 election, only 51.4% of eligible voters went to the polls, compared to 60.1% nationally.

There are several reasons why Texas’s voter turnout rate is so much lower than the national average. Texas is ranked as the state with the fifth highest difficulty of voting, according to a Northern Illinois University study that considered factors such as the registration deadline, restrictions on who is able to vote, ease of registration, the availability of early voting, voter ID laws, and poll hours.

But voting difficulty does not fully explain Texas’s low turnout rate. It is even more difficult to vote Virginia than it is in Texas. Nevertheless, in 2016, despite obstacles to getting to the polls, voter turnout in Virginia 66.1%.

The difference is not that Virginians are more civic minded, or that Texans are lazy. The differences is that, in recent elections, Virginians were told that their votes count more than Texans’ votes. In 2016, the presidential candidates hosted a total of 23 events in Virginia—the fifth highest of any state. The 2012 campaigns spent $21.6 million on advertising in Virginia—the third highest of any state. Meanwhile, both parties ignored Texas, making little to no effort to court its voters.

However, in 2000, Virginia’s voter turnout was only 55.0%. In the intervening years, Virginia shifted from a solidly Republican state to a swing state. The increase in voter turnout in Virginia demonstrates that, even in states where it is very difficult to vote, people will make the effort if their votes may make a difference. On the other hand, many Texans determined that it is not worth their time to vote for president because the result seemed pre-ordained. Though Texas and Virginia present particularly striking examples, voter turnout is generally lower in non-battleground states than in swing states lavished with the candidate’s attention.

But things are changing yet again. Both parties may decide that Virginia is a safe state for the Democrats in 2020, and not bother visiting or spending money on ads and get-out-the-vote efforts. In Texas, on the other hand, there is more and more talk that the old Republican stronghold may be shifting toward swing state status. Accordingly, voter participation in Texas is likely to rise, but may fall in Virginia.

Wouldn’t it be better if every vote counted equally, no matter whether your state was a swing state in a given election? Under a national popular vote, 20 million or more voters as turnout surged across the country.

It is Also About Where they Live

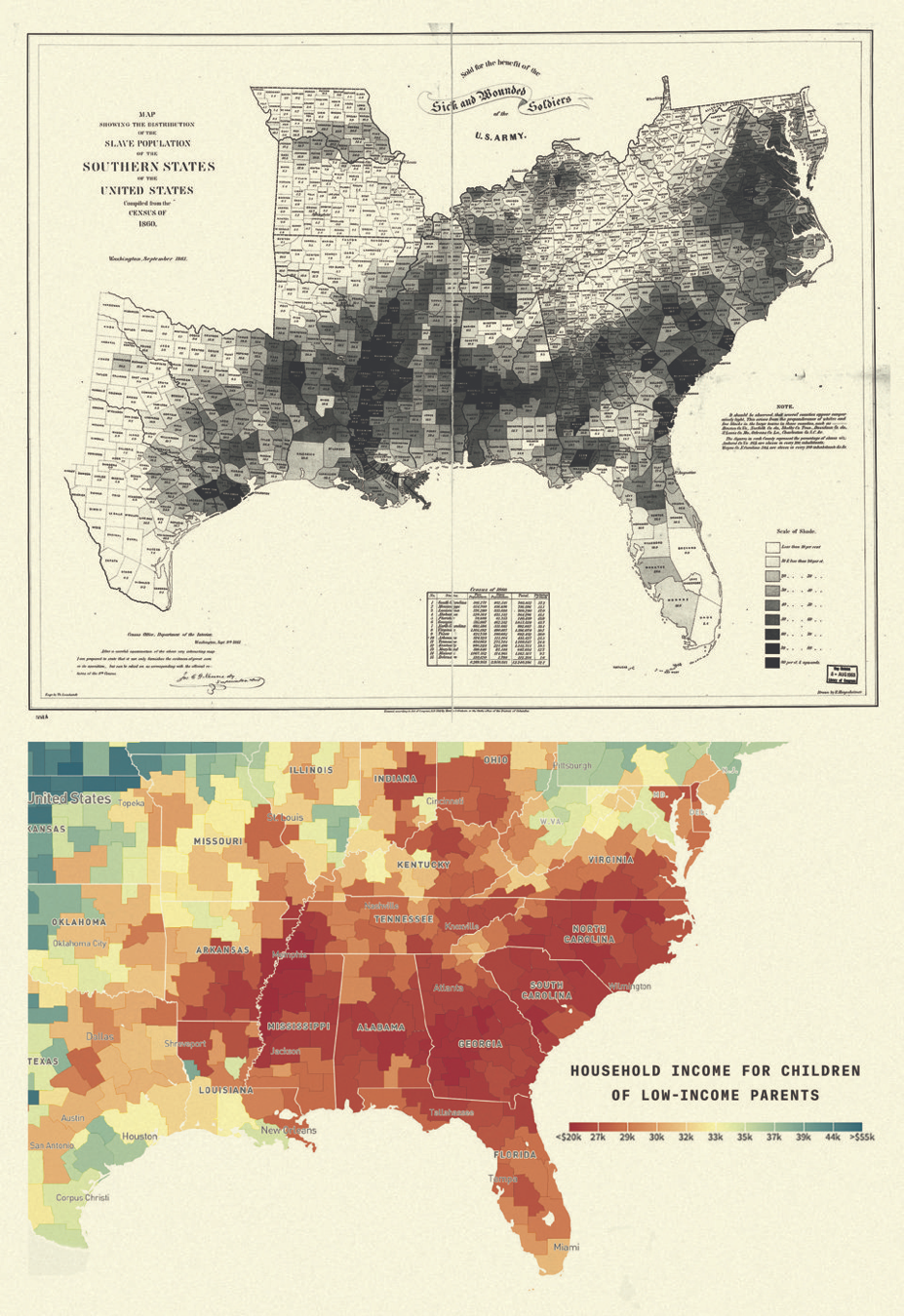

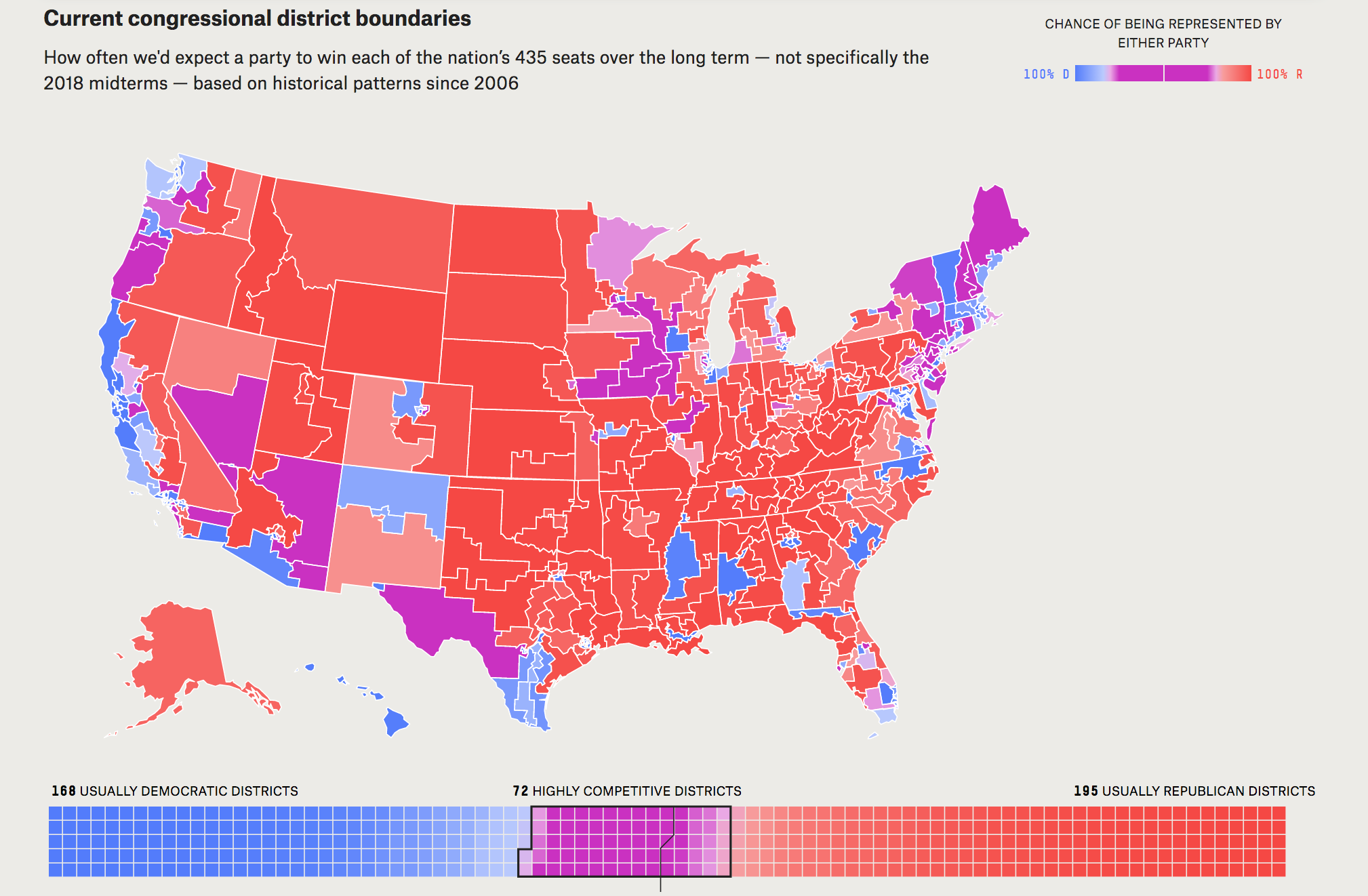

This chart from the New York Times shows something very important but leaves out the key fact. Again and again political reporters leave this out.

The electoral college system does not magnify every political faction. It minimizes some, such as college educated (also high turnout) or African Americans. It magnifies white evangelicals because of their large presence in the few midwestern swing states, where their voting exceeds 30%:

Presidential elections are about the past

A truism in politics is that elections are about the future. Typically the change candidate wins.

But actually with the broken system that prevails in the United States the presidential election is more about the past. The backwards looking candidate is advantaged.

As the chart below shows the states where America is changing the most rapidly are almost all irrelevant to the outcome of the presidential election.

Thanks, Electoral College

Almost all the voters in the problem locations below are ignored by the system. Florida, it gets attention, and sometimes North Carolina. But the candidates in both parties take for granted the outcome all the rest of these states. Given the plight of the people in these states, the voters really ought to be able to have all their votes count in a national election of the president.

There are two maps shown. The first is Lincoln’s, used to inform him about the slave population. The second, is Raj Chetty’s report on where low income parents are located. The overlaps show, among other things, how long the Electoral College system has denied voice to the people – of all races! – in these states.

Listening to voters

According to this article, politicians pay attention to voters. The problem with a president, however, is that to get a second term it is only important to pay attention to the voters in the swing states. More than 80% of the voters are ignored because they are in states where the results are taken for granted.

Here's Why Splitting Electoral Votes Proportionally Is Not the Answer

In another post, we discussed the problems with dividing a state’s electoral votes by congressional district (in a word: gerrymandering). Another proposed solution to the winner-take-all problem is allocating electors proportionally based on the votes of the state at large. Simply put, if a candidate won 70%-30% in a state with 10 electoral votes, 7 votes would go to the winner and 3 to the runner-up.

The upsides of this proposal are straightforward: more votes would matter, turnout would increase, and candidates would have incentives to seek votes in more places. But proportional representation is unlikely to create a national campaign, nor would it make every vote truly equal. Indeed, a proportional system may lead to an even more undemocratic result than is likely under our current system.

While there would be fewer wasted votes under a proportional system, it would not make every vote count. Absent a constitutional amendment, the votes would have to be rounded to the nearest whole elector. So there would still be wasted surplus votes and votes for the runner up that do not count in the final tally. In close elections, this could lead to the winner of the national popular vote still losing the presidency.

But splitting electoral votes proportionally would raise a whole new problem: a dramatic increase in the likelihood of third-party candidates throwing the election to the House of Representatives.

If a third-party candidate could get enough votes to win just a few electors in a close election, that candidate could prevent anyone from reaching the 270 electoral votes necessary to win. In such a case, the election would go to the House of Representatives, with each state getting a single vote regardless of population. This is a profoundly undemocratic outcome that would lead to voters losing their voices entirely.

Looking at past elections, the House would have decided the outcome in at least 2000 and 2016 if electors were awarded proportionally. But if elections actually occurred under the proportional system, the percentage of elections decided by the House would be much higher as the incentives for third-party candidates grew exponentially. In large states, a third-party candidate would be able to garner at least a couple of electoral votes by winning only a tiny fraction of the vote in that state, and in a close election, that could keep any party from reaching 270.

Once the vote goes to the House, horse-trading, corruption, and backroom deals could lead to a candidate being inaugurated despite having little popular support. So proportional representation is not cure for the evils in our system and would create a host of new and bigger problems.

There is also a feasibility problem under any proposal that involves splitting votes. Unless all or almost all states signed on, the campaigns would still not be truly national—and many states will be unwilling to split their votes for fear of losing political influence.

Splitting up a state’s electoral votes makes sense for a few small states—like Maine and Nebraska—that are perpetually ignored. But most states adopted a winner-take-all system in order to increase their political heft. They wanted candidates to campaign in their states in hopes of winning a large number of electoral votes at once. Therefore, states will be unlikely to unilaterally split their votes for fear of losing that clout.

Safe states would hesitate to give up any of their votes to the other party, and swing states would hesitate to lose their special status. And as long as just a few big swing states kept the winner-take-all system, candidates would have a strong incentive to focus their campaigns on those states alone rather than battling it out for the one or two swing electoral votes in most other states.

The best way to make every vote count—and to make presidential candidates campaign for every vote—is to enact the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. Unlike splitting electoral votes, no state is put in the position of unilaterally giving up any influence because the Compact does not go into effect until enough states join to guarantee the winner of the national popular vote will become the president. And the Compact is over 70% of the way there—only a few more states need to sign on to make it a reality. When that happens, all votes will count equally—no matter where you live.

Youth must be served

As this article explains, voter turnout among youths can be decisive in elections.

But the electoral college system in this century is biased against young voters. Why? Swing states such as Florida, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, have some of the highest median ages in the country:

The key swing states Florida and Pennsylvania have the first and second highest percentage of residents over the age of 65. Voters in these older states decide the election and the young people everywhere else are taken for granted.

It’s the system

The point is that the Electoral College system motivates the candidates from the major parties not to move to the center of the country. Instead, they should and must focus only on what drives turn out in a handful of states that are not necessarily representative of the rest of the nation.

Here a New York Times columnist plumps for anyone but the incumbent, but misses the point of what the system causes to happen:

“A majority of the American electorate — liberals, moderates and even some conservatives — want a greater government role in health care, a higher minimum wage, higher taxes on the rich and less punitive border policies. If Trump isn’t going to move to the center, then their only choice should be the party that, no matter its nominee, backs each item on that list.”

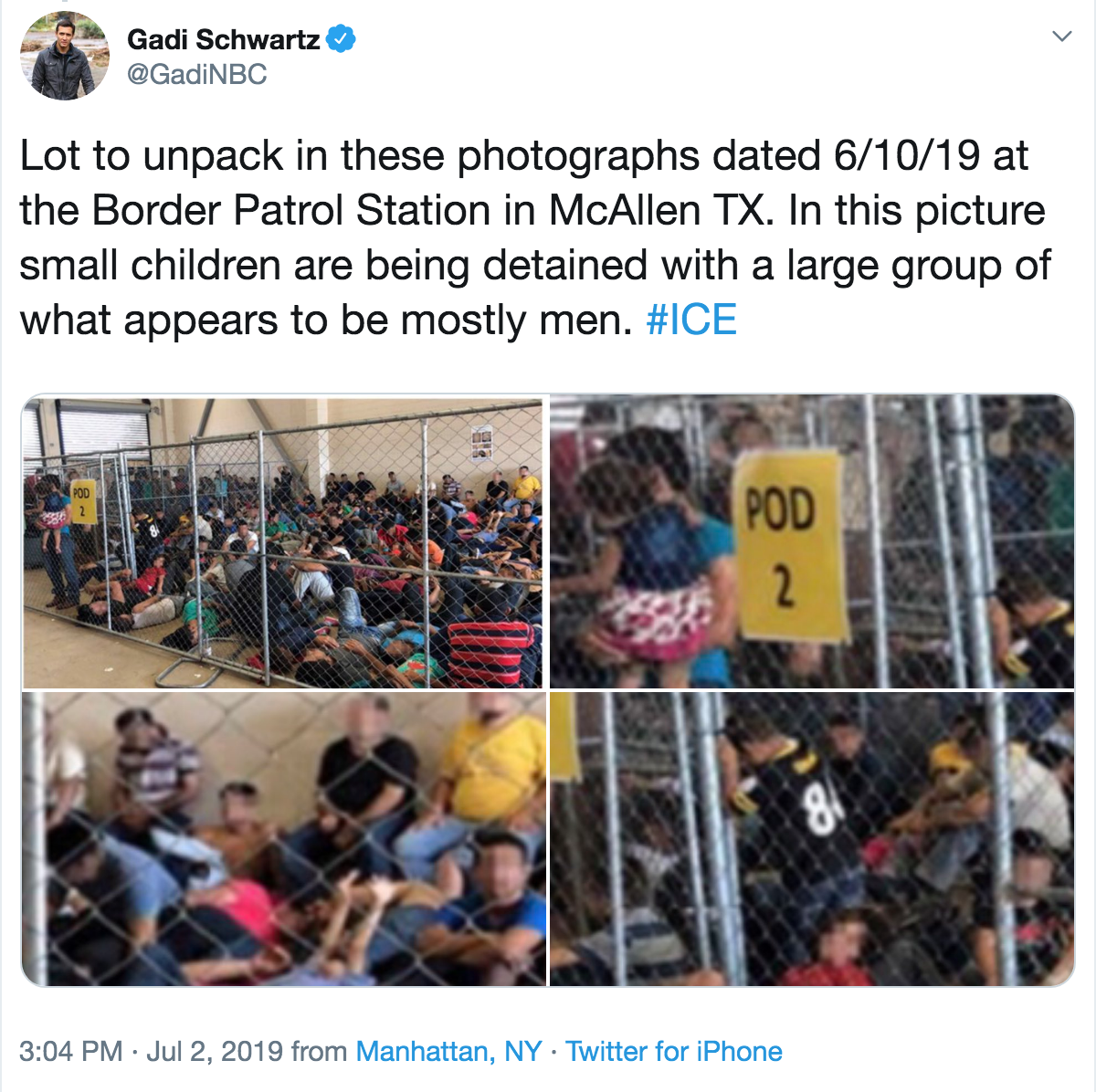

Electoral College Treats Children Cruelly

No president who needed to win the national vote for re-election would tolerate this:

Who cares what most people want?

It never even crosses the mind of the CBS reporter or the Trump campaign manager that most people in the country disapprove of the president.

In America’s screwy system, that doesn’t matter. Donald Trump only needs to win Florida to be in the re-election catbird seat. That’s why he kicks off his campaign there. No one comments about that either. It is taken for granted that the president should be reelected or not based on whether he gains a narrow plurality from people in Florida and a couple other swing states.

Then his campaign manager talks about a “landslide” consisting of winning by a few votes a couple of very tiny states that Trump did not carry in 2016. This is a landslide composed of a couple of pebbles.

Donald Trump currently holds the record for consistent disapproval. No matter. Unless a few states change the way the electors are picked, most Americans don’t matter in picking the president. This is the reason why it was dreadful that the governor of Nevada vetoed the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. He could’ve been part of the most important reform in the political process. He could have been somebody.

Electoral college reform matters more than ever

The Supreme Court’s decision to bar the federal judiciary from addressing partisan gerrymandering lets state legislatures deprive blocks of voters from congressional representation — subject only to review by state courts whose members are confirmed by the same legislatures or possibly elected through the same gerrymandering.

Republicans in Maryland or African Americans in North Carolina are just two examples of the victimized groups.

This ruling opens the door for states to adopt a district system for choosing electors that would gerrymander picking the president.

While the Supreme Court continues to make its negative contributions to the survival of the American republic, it is even more important that every American voter counts and counts equally in electing the president of the United States. Then a future president, one who wins the national plurality, might appoint justices who are committed to promoting democracy.

Politicians, donors, and voters really have to get on board the national popular vote train. The country is in a bad fix.

It’s a shame that the Democratic legislatures just frustrated reform in Maine and the governor of Nevada vetoed the reform bill. Dems be woke please.

Here's Why Splitting Electoral Votes by Congressional District is Not The Answer

The problems with the way we choose our president are numerous and severe, including:

disproportionate attention to swing states (both during and after elections);

effective disenfranchisement of citizens who live in “safe” states for one party but prefer another party, leading to low turnout;

threats to our national security due the small number of states a foreign hacker can target to change the outcome of the election;

the fact that the winner of the election may not be the person who got the most votes—an outcome that we will see more and more.

Some people, recognizing the seriousness of the problems with our system, have suggested an alternative: allocating electoral votes by congressional districts instead of giving all of a state’s votes to the plurality winner.

Each state has a number of electors equal to its representation in Congress—two votes for the Senate, and a number that varies based on the state’s population for the House. Under this proposed system, each state would allocate two votes at large for the overall winner of the state and the rest of the electors would go to the candidate that wins each of the congressional districts. This is how Maine and Nebraska allocate their electoral votes.

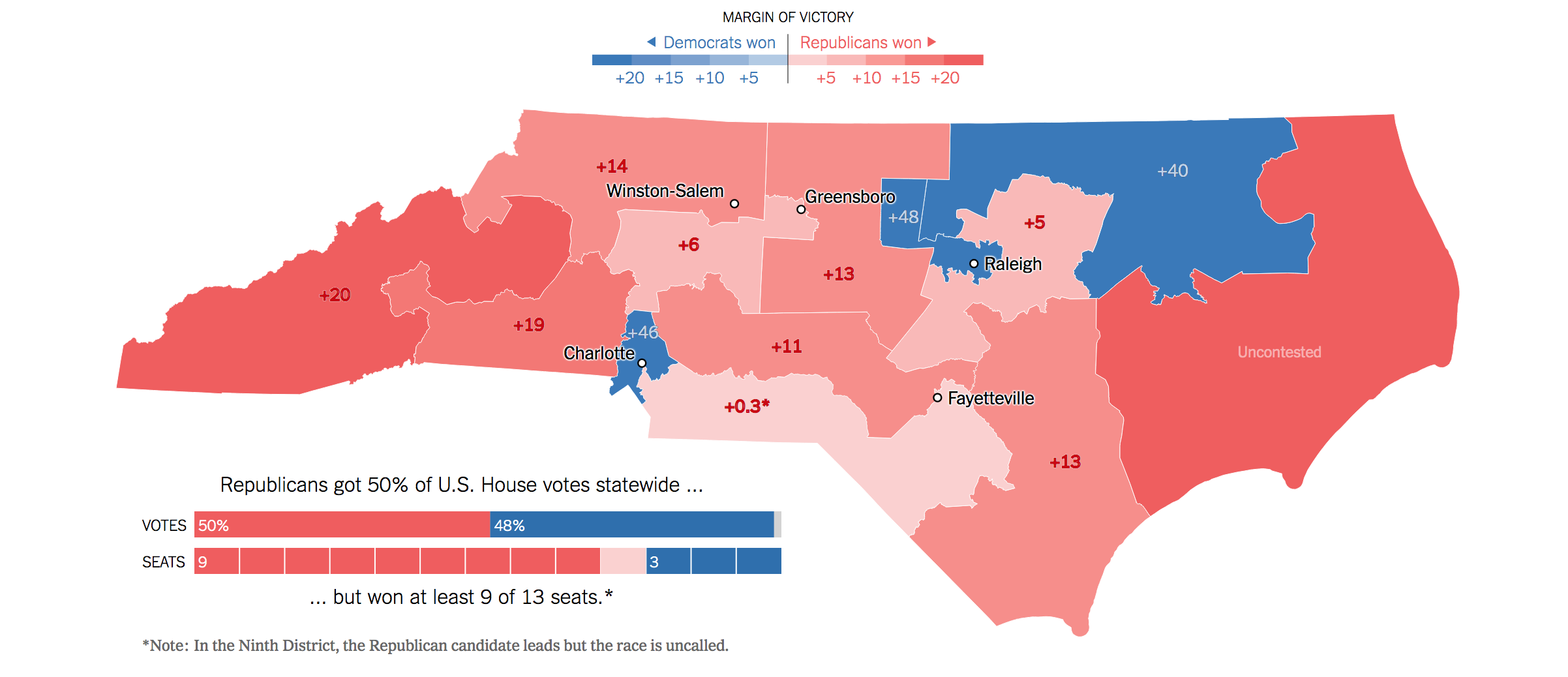

Proponents of this system argue that it would be more fair, and that it would be less likely to result in a candidate winning the national popular vote while losing the Electoral College. However, this is not true for one simple reason: gerrymandering.

Gerrymandering is a serious problem with our representative system. For example, in 2016 and 2018, Republican congressional candidates in North Carolina won about 50% of the congressional votes in that state, but claimed victory in 10 out of the states 13 districts (the Ninth District will have to vote again following election fraud in 2018).

Under this map, a Democratic candidate could get a plurality of votes in North Carolina (as Obama did in 2008) but still only be awarded only 5 out of the state’s 13 electoral votes (winning in 3 districts plus the 2 at-large votes).

Because of gerrymandering, allocating electors by congressional district will actually be more likely to result in popular vote losers becoming president than the current system. If the 2012 election had been decided based on congressional districts, Mitt Romney would have defeated Barack Obama in the Electoral College 274-264, despite losing the popular vote by nearly five million votes. Donald Trump also would have won under this system in 2016 despite losing the popular vote. The incentive to gerrymander would increase exponentially if congressional districts determined control of the White House as well as control of the House, making the problem even worse than it is now.

As candidates adjusted their strategy to focus on the 16% of districts that are “swing” districts, a split between the popular vote and the electoral college will be even more likely.

The vast majority of voters would live in “safe” districts, meaning that most people still would have little incentive to turn out to vote and their concerns and issues will be ignored as they lose out on federal funding to swing districts. The swing districts will become the new target for election meddlers.

Proponents of district-based electoral allocation recognize that gerrymandering would have to be addressed before the system would be fair. However, the Supreme Court has refused to address partisan gerrymandering, no matter how egregious.

Accordingly, allocation of electors based on congressional districts would only make elections more unfair and would not solve the problems with our current system.

Electoral college doesn’t like health care

The electoral system is the reason why these red states get away with not expanding Medicare. Why? Because candidates in both parties don’t campaign there. The pluralities are foregone conclusions. Those who suffer don’t count because rural poor are outvoted by suburban voters, and they aren’t permitted by the system to vote with similarly affected people in other states.

Impossible

If the national popular vote chose the president, it would be impossible for a president seeking a second term to block the printing of the following:

Such a move would cost too many votes.

Under the current system, most of the aggrieved, those who are meant to be recognized by this image commissioned by the Obama Administration, are in states where they are outvoted by a majority of a different race, and so they have no weight in the calculus of winning the general election for president.

Think the Electoral College benefits small and rural states? Not so fast.

Conventional wisdom says that a national popular vote will harm the interests of small, rural states. It is true that because a state’s electoral votes equal its representation in the House plus two votes for each Senator, small states do have a slightly higher share of Electoral College votes than they would have if the votes were distributed in accordance to population alone.

But how much does that really matter? The fact that Idaho has four electoral votes instead of two does not mean that candidates try to win any votes in Idaho. No candidate visited the state in 2016, nor did candidates flood the airwaves with ads, nor did they discuss policy issues of particular concern to Idaho, nor did they set up extensive get-out-the-vote operations. As a result, only 59.2% of eligible voters in Idaho voted for president in 2016. Rhode Island, which also has four electoral votes, was similarly ignored completely by candidates and, not surprisingly, had correspondingly low turnout of 59.1%.

On the other hand, New Hampshire, which has the same number of electoral votes as Idaho and Rhode Island, got 21 visits from candidates in 2016, plus countless ads and a serious get-out-the vote effort. Not surprisingly, turnout for the presidential election in New Hampshire was 71.4%—the second highest in the nation.

The differing treatment of New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Idaho is explained by the fact that New Hampshire is a swing state while Rhode Island and Idaho are not.

New Hampshire gets attention in spite of the fact that it is small, not because it is small.

In a piece in Bloomberg, Justin Fox explains that in the 1960s and 1970s, people criticized the Electoral College because it unfairly gave an advantage to big states and big cities, at the expense of small states. That’s because back then, the five biggest states—New York, California, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Ohio—were all swing states. As Fox notes, any advantages conferred by the system to big states, to Republicans, or to Democrats, are transient:

It’s easy enough to look back at a presidential election and determine how the Electoral College hurt or helped your side. It’s a little harder, but far from impossible, to come up with reasonable suppositions about which states will play a more or less decisive role in an impending election. Determining who the Electoral College helps or hurts over the long run, though, may be too tough a puzzle for anyone to solve.

...

The best way to think of the Electoral College may be as a wrench that occasionally gets thrown into the works of American presidential elections, delivering a result that is at odds with the popular vote. I would beware of becoming too confident that said wrench is on your side.

In other words, the only constant of the Electoral College is that it benefits swing states. Most small states, like most big states, get ignored.

And if you don’t live in a swing state, the consequences go far beyond how many ads you are likely to see in an election year. Your industries get ignored, your funding gets cut, and you are less likely to get disaster relief funding than people who live in the handful of states that decide elections.

Oregon Officially Joins National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

Oregon governor Kate Brown has signed the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact into law, making Oregon the 16th jurisdiction to join the agreement that will guarantee that the winner of the popular vote will also win the electoral college.

The Constitution gives each state the power to award its electoral college votes as it sees fit. Right now, all states give their electoral votes to the plurality winner of that state (except Nebraska and Maine). However, under the Compact, each member state will give its votes to the winner of the national popular vote.

The Compact will not go into effect until states with 270 total electoral votes join—the number needed to secure a majority of electoral college votes. Accordingly, the states will not award their electoral college votes to the winner of the national popular vote until there are enough electoral votes pledged to guarantee the winner of the national popular vote becomes president.

Right now, the Compact has 196 votes committed, including Oregon. In order to reach 270, there will have to be a massive public education campaign to show voters that this issue is bigger than partisan politics. The fact that almost every state gives its votes to the plurality winner has serious consequences, including:

disproportionate attention to swing states (both during and after elections), meaning that those states get more disaster relief funding, money for special projects, and more attention to industries concentrated in those states;

effective disenfranchisement of citizens who live in “safe” states, leading to low turnout;

threats to our national security due the small number of states a foreign hacker can target to change the outcome of the election;

the fact that the winner of the election may not be the person who got the most votes—an outcome that we will see more and more.

The electoral college will sometimes favor Democrats and sometimes Republicans, but in the long run, everyone will be better off if Americans can choose their leader directly, and every person’s vote counts equally.