In his editorial, “The Lovely but Unloved Electoral College,” appearing in the April 10, 2019 Wall Street Journal, former George W. Bush strategist Karl Rove does not so much defend the Electoral College but attempts to minimize its failings and paints a parade of horribles that he imagines would descend if the system were altered. If anything, much of his defense of the current system is an argument for its alteration.

First, Rove states that there is “zero chance” of abolishing the Electoral College because it would take a constitutional amendment. While he is correct that an amendment is unlikely, he is wrong that there is no other way for the system to change. The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is an agreement among states to give their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote once states with 270 electoral votes join the Compact. Right now, fourteen states plus DC have passed the Compact, totaling 189 votes—70% of the way to becoming effective. There is tremendous momentum behind the Compact, with Oregon likely to be the next state to join with 7 additional electoral votes.

Rove does not argue that it is good that the Electoral College sometimes means a person becomes president despite the fact that more voters preferred another candidate. Instead, he argues that splits between the Electoral College and the national popular vote are a “rare divergence” explained by “extenuating circumstances.”

But these “circumstances” are in fact strong arguments for reform. He argues that the only reason George W. Bush lost the popular vote in 2000 is because the TV networks prematurely called Florida for Gore at 8:02 Eastern time, while many western states were still voting. Rove does not provide a citation for his assertion that “Republicans were more likely to be discouraged and stay home, probably costing George W. Bush several hundred thousand votes and two states, New Mexico and Oregon,” but even if it were true, this is a good reason why the country would do better under the popular vote. If all votes count equally, it will be much more difficult for networks or other actors to interfere with the results, intentionally or otherwise, while votes are still being cast.

Rove also asserts that “Winning GOP candidates may have fallen short in the popular vote in 1876 and 1888 only because the black Republican vote in the South was being extinguished by violence.” What he doesn’t mention is how the Electoral College meant that even if they had been able to vote, the votes of African Americans in the south would not have counted because they could not get a plurality in the states where they lived, a problem that persists to this day.

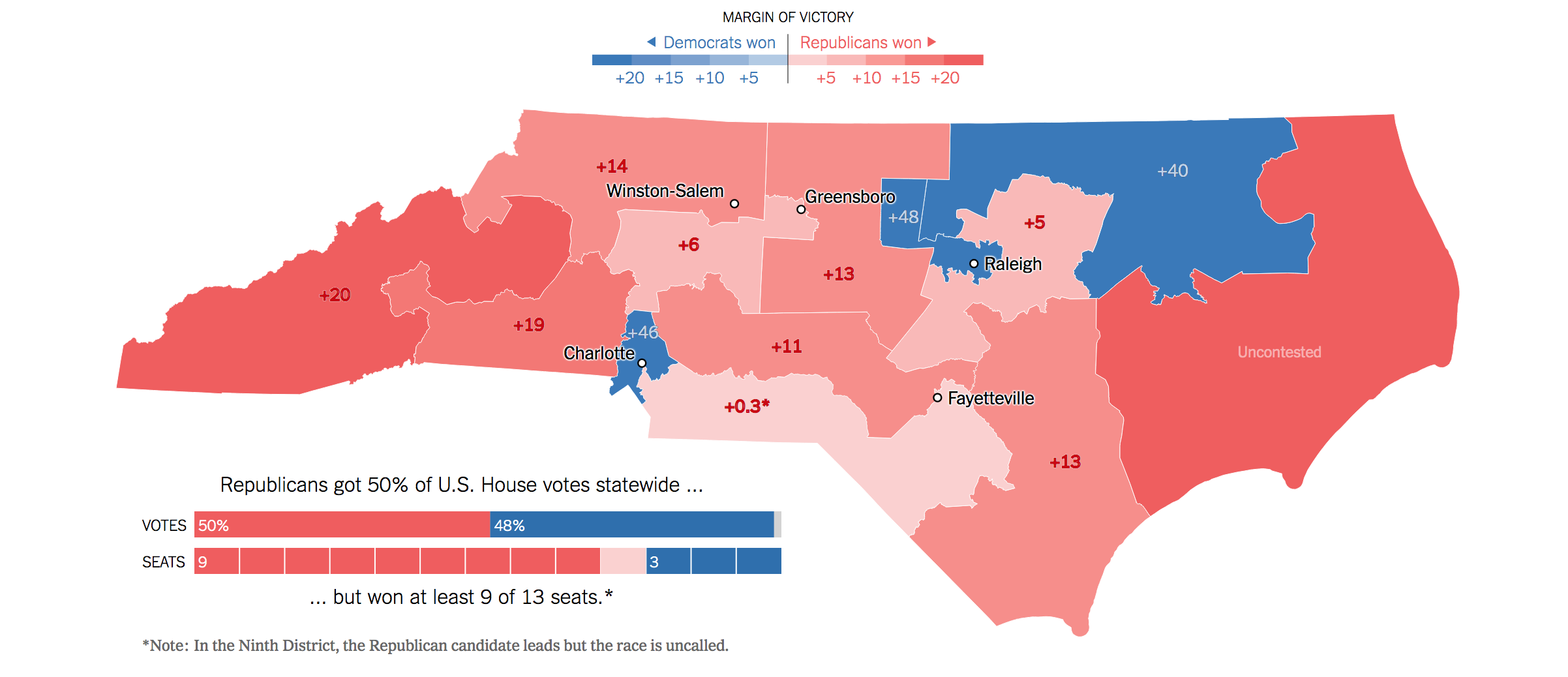

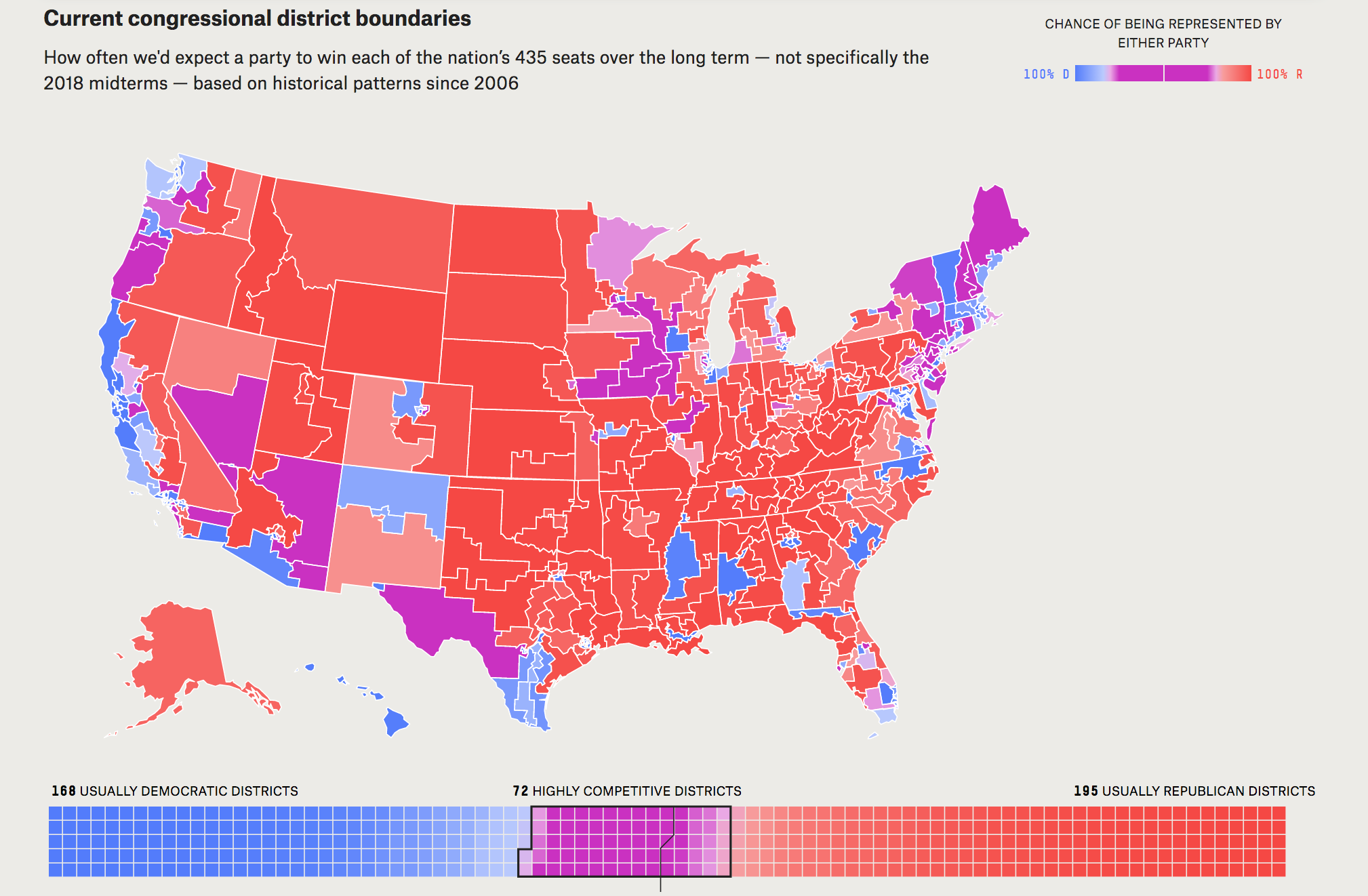

More important than past elections is the likelihood that the Electoral College will thwart the will of the people in the future. Rove notes that there have only been five Electoral College/popular vote splits out of 58 elections, but fails to note that splits have occurred in two out of the last five elections, and two out of the last three open elections. Our analysis shows that, far from becoming more and more rare, splits will become increasingly likely when the outcome rests on just a few swing states. In close elections, there will be a split in up to 32% of elections, with neither party having a long-term advantage.

Next, Rove suggests that a number of consequences would befall our nation if we switched to a national popular vote: there would be recounts needed in many states, third parties would multiply, and small states would be ignored. But those are all problems that exist in a worse form under the current system than under a popular vote.

A popular vote election involving hundreds of millions of voters would be unlikely to be close enough to need multiple recounts, unlike the winner-take-all Electoral College where the election can turn on a few hundred voters in a single state.

Right now, a third party candidate could theoretically win the election with only 23% of the vote. Under a popular vote, a third party would at least have to get more votes than anyone else. Further, many Americans feel disenchanted with the two major parties and would welcome real third party challenges, perhaps in combination with ranked-choice voting.

Finally, small states, as well as most big and medium-sized states, are already ignored by candidates who instead lavish almost all of their attention on big swing states like Florida and Pennsylvania.

Rove claims that “[t]he Founders knew what they were doing. Abolishing the Electoral College is an awful idea.” But though the Founders were brilliant men, they were not omniscient. They came up with a compromise that reached the necessary votes—and that was constrained by the hard limits on travel and communications at the time—but which they themselves acknowledged was not perfect. More importantly, it bore very little resemblance to the Electoral College as it operates now. It was, according to Hamilton, meant to be a deliberative body of a “small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, [who] will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations” as choosing the president. Of course, the reality is far different.

It is time to work within the confines of the Constitution to allow the people to choose the president. Article II, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution allows the states to determine how electors are appointed. If state law in enough jurisdictions directed the electors to pledge their votes to the winner of the national popular vote, campaigns would have to look everywhere for votes instead of focusing on a few swing states. Only then will every vote matter equally.