In his book “No Property in Man,” historian Sean Wilentz writes of the Constitution’s Framers, “On July 20, the delegates gave their initial approval to what might have been the most decisive triumph on behalf of slavery of the entire convention….the creation of the Electoral College.” Page 70.

The Electoral College was conceived in the sin of slavery. No one now argues that slavery was anything other than a horrible proof of the depravity of human beings. Holding on to it was the single strongest motive of the southerners at the convention.

As Wilentz writes, “the convention divided between those more and those less impressed by the competence of popular rule,” but beyond doubt “southerners in both groups had an additional reason to oppose popular election of the president.”

What was that? And does it still lurk in the thinking of those who oppose direct election by national popular vote of the president? See, e.g., former Maine Governor Paul LePage, who oppose direct election because it would empower non-white voters.

Wilentz explains that because slaves would not be able to vote, “southerners were unlikely ever to win the presidency under a democratic system.”

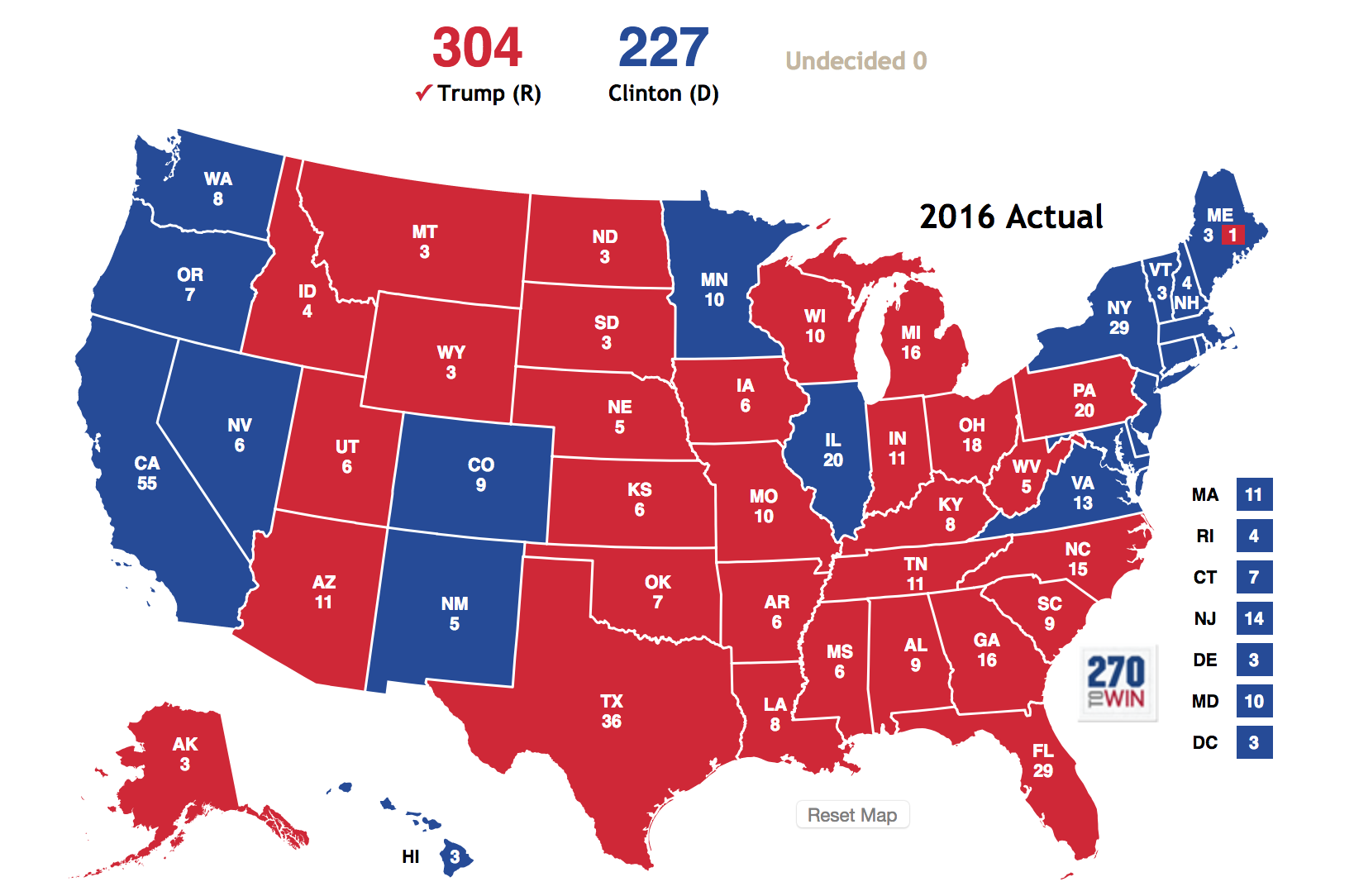

Even today, more than 200 years later, African American voters in the south typically play little to no role in the general election of the president – because the electoral system systematically discards the votes for runners-up, which usually is where the non-white vote in the polarized south goes:

To win the southern states’ agreement to vote for the constitution, Madison apportioned the electors according to total of the seats in the House, which gave weight to slaves on a three-fifths basis, and seats in the Senate, which gave weight to relatively underpopulated states (which came to include more slave states, like the nearly empty Florida and Arkansas). The unsurprising result, Wilentz explains, was that “four of the first six presidents of the United States were Virginia slaveholders.” He might have gone on to say that no president was anti-slavery until Abraham Lincoln in 1860. And Lincoln won only because the Democratic Party split between northern and southern factions.

The history of America is the history of race and the principal arguments for the Electoral College system today are, whether or not well-intentioned, all too clearly resonant of the views of the southern delegates in the 18th century and Governor LePage this week.